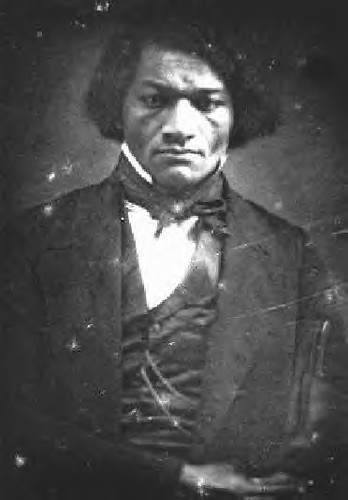

Frederick Douglass, anti-slavery organizer and journalist. His July 5, 1852 speech in Rochester, New York is still cited some 161 years later., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

What 'Lincoln' misses and another Civil War film gets right

By John Blake , CNN

updated 2:34 PM EST, Tue January 8, 2013

(CNN) -- He used the N-word and told racist jokes. He once said African-Americans were inferior to whites. He proposed ending slavery by shipping willing slaves back to Africa.

Meet Abraham Lincoln, "The Great Emancipator" who "freed" the slaves.

That's not the version of Lincoln we get from Steven Spielberg's movie "Lincoln." But there's another film that fills in the historical gaps left by Spielberg and challenges conventional wisdom about Lincoln and the Civil War.

"The Abolitionists" is a PBS American Experience film premièring Tuesday that focuses on the intertwined lives of five abolitionist leaders. These men and women arguably did as much -- maybe even more -- than Lincoln to end slavery, yet few contemporary Americans recognize their names.

The three-part documentary's airing comes as the nation commemorates the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, the 1863 decree signed by Lincoln that set in motion the freeing of slaves. Lincoln is a Mount Rushmore figure today, but the abolitionists also did something remarkable. They took on the colossal wealth and political power of the slave trade, and won. (Imagine activists today persuading the country to shut down Apple and Google because they deem their business practices immoral.)

The abolitionists "forced the issue of slavery on to the national agenda," says Sharon Grimberg, executive producer for the PBS documentary. "They made it unavoidable."

"The Abolitionists" offers four surprising revelations about how the abolitionists triumphed, and how they pioneered many of the same tactics protest movements use today.

No. 1: The Great Persuader was not Lincoln

Near the end of "Lincoln," Spielberg shows the president delivering his second inaugural address, a majestic speech marked by harsh biblical language. Lincoln is often considered to be the nation's greatest president in part because of such speeches. He was an extraordinary writer.

But the most well-known condemnation of slavery during that era didn't come from the pen of Lincoln. It came from the pen of Harriet Beecher Stowe, the daughter of a Presbyterian minister who joined the abolitionist movement, the PBS film says.

Stowe's "Uncle Tom's Cabin" awakened the nation to the horrors of slavery more than any other speech or book of that era, some historians say. It hit the American public like a meteor when it was published in 1852. Some historians say it started the Civil War.

The novel revolved around a slave called Tom, who attempted to preserve his faith and family amid the brutality of slavery. The book became a massive best-seller and was turned into a popular play. Even people who cared nothing about slavery became furious when they read or saw "Uncle Tom's Cabin"' performed on stage, the documentary reveals.

The lesson: Appeal to people's emotion, not their rationale, when trying to rally public opinion.

Abolitionists had tried to rouse the conscience of Americans for years by appealing to their Christian and Democratic sensibilities. They largely failed. But Stowe's novel did something all those speeches didn't do. It told a story. She transformed slaves into sympathetic human beings who were pious, courageous and loved their children and spouses.

"When abolitionists were talking about the Constitution and big ideas about freedom and liberty, that's abstract," says R. Blakeslee Gilpin, a University of South Carolina history professor featured in "The Abolitionists."

"But Stowe begins with the human dimension. She shows the human victims from the institution of slavery."

150 years later, myths persist about the Emancipation Proclamation

No. 2: It's the economy, stupid

Want to know why slavery lasted so long? The simplistic answer: racism. Another huge factor: greed, according to "The Abolitionists."

Many abolitionists didn't realize this when they launched the anti-slavery movement, the documentary shows. They were motivated by Christian idealism, but it was no match for the power of money.

Christianity and slavery were two of the big growth industries in early America. The country underwent two "Great Awakenings" in the early 19th century -- while slavery continued to spread.

But the spread of Christianity did little to stop the spread of slavery because too many Americans made money off slavery, the documentary shows. The wealth produced by slavery transformed the United States from an economic backwater into an economic and military dynamo, says Gilpin, also author of "John Brown Still Lives!: America's Long Reckoning With Violence, Equality, and Change."

"All the combined economic value of industry, land and banking did not equal the value of humans held as property in the South," Gilpin says.

Many Americans hated abolitionists because they saw them as a threat to prosperity, says David Blight, a Yale University historian featured in "The Abolitionists."

"They wondered if you really did destroy slavery, where would all of these black people go, and whose jobs would they take," says Blight.

The South wasn't the only region that profited off the slave trade. Abolitionists faced some of their most vicious opposition in the North. New York City, for example, was a pro-slavery town because it was filled with bankers and cotton merchants who benefited from slavery, Blight says.

"Jim Crow laws did not originate in the South; they originated in the North," Blight says.

The lesson: Don't reduce the issue of slavery to racism. Follow the money.

No. 3: Flawed reformers

The historian Henry Louis Gates Jr. once said that black abolitionists used to say that the only thing white abolitionists hated more than slavery was the slave.

"The Abolitionists" reveals that some of the most courageous anti-slavery activists were infected with the same white supremacist attitudes they crusaded against. White supremacy was so ingrained in early America that very few escaped its taint, even the most noble.

The documentary shows how racial tensions destroyed the friendship between two of the most famous abolitionists: Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison. Garrison was the editor of an abolitionist newspaper who convinced Douglass that he could be a leading spokesman against the institution that once held him captive.

Erica Armstrong Dunbar, a history professor featured in the film, says some abolitionists were uncomfortable with interracial relationships. They wouldn't walk with black acquaintances in public during the day, and refused to sit with them in church.

Lesson: Racism was so embedded in 19th century America that even those who fought against racism were unaware that it still had a hold on them.

"The majority of aboloitionists did not believe in civic equality for blacks," Dunbar says. "They believed the institution of slavery was immoral, but questions about whether blacks were equal, let alone deserved the right to vote, were an entirely different subject."

No. 4: Lincoln the "recovering racist"

Tell some historians that "Lincoln freed the slaves" and one can virtually see the smoke come out of their ears.

"Please don't get me started," Dunbar says after hearing that phrase.

"There's this perception that good old Lincoln and a few others gave freedom to black people. The real story is that black people and people like Douglass wrestled their freedom away," Dunbar says.

Historians still argue over Lincoln's racial attitudes. The historian Henry Louis Gates Jr. once called him a "recovering racist" who used the N-word and liked black minstrel shows.

Others point to the public comments Lincoln made during one of his famed senatorial debates with Stephen Douglas in 1858 when he said, "There is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality.

"There must be the position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race," Lincoln said in the speech.

Spielberg's film depicts Lincoln as a resolute opponent of slavery, willing to deploy all the powers of his office to destroy it.

Yet "The Abolitionists" paints another portrait of Lincoln. It recounts how he supported colonization plans to ship willing slaves back to Africa. It says that Lincoln once floated a peace treaty offer to the Confederates that would allow them to keep slaves until 1900 if they surrendered. At one White House meeting with black ministers, Lincoln virtually blamed slaves for starting the war, the film's narrator says.

Blight, the Yale University historian, says Lincoln always personally hated slavery. He publicly spoke out against it as early as the 1840s, and spoke often about stopping the expansion of slavery.

Lincoln hoped to slowly end slavery without tearing the nation apart, Blight says.

"He was a gradualist," Blight says. "He was trying to prevent a bloody revolution over it. He couldn't."

He couldn't because of the pressure exerted by the abolitionists and the slaves themselves, other historians say. Blacks did not wait for white people to free them, they say. At least 180,000 blacks fought in the Civil War. And Douglass was one of Lincoln's harshest critics. He constantly pushed Lincoln to move aggressively against slavery.

The historian William Jelani Cobb wrote in a recent New Yorker essay on slavery:

"On the hundred-and-fiftieth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, it's worth recalling that slavery was made unsustainable largely through the efforts of those who were enslaved. The record is replete with enslaved blacks—even so-called house slaves—who poisoned slaveholders, destroyed crops, 'accidentally' burned down buildings."

As for Lincoln's true feelings about blacks, that matter may always be subject to debate.

"No historian would doubt that Lincoln was a man of his times," says Dunbar, author of "A Fragile Freedom: African American Women and Emancipation in the Antebellum City." "He was a racist, and never truly believed that blacks could live in America after emancipation."

Other historians say Lincoln was evolving into the leader that Spielberg depicts.

The historian Gates once wrote that Lincoln initially opposed slavery because it was an economic institution that discriminated against white men who couldn't afford slaves. Two things changed him: The courage black troops displayed in the Civil War and his friendship with Douglass the abolitionist.

"Lincoln met with Douglass at the White House three times. He was the first black person Lincoln treated as an intellectual equal, and he grew to admire him and value his opinion," Gates wrote.

Gilpin says Lincoln was great not only for what he got right, but because he could admit what he got wrong.

"You dream of a president like that," Gilpin says. "Not only was he a brilliant manipulator and reader of public opinion, but he had the capacity for growth. He came into office because he was a moderate but he turns out to be the Great Emancipator."

Lesson: Lincoln led an epic battle against slavery, but the abolitionists lit the fuse.

No comments:

Post a Comment