1906 ATLANTA RACE RIOT

A century later, a city remembers

By Jim Auchmutey

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Published on: 09/17/06

On a cloudy Monday night a century ago this month, a dozen white lawmen and armed civilians marched into Brownsville, a black neighborhood on the southern edge of Atlanta, and started arresting anyone with a weapon.

It was the third day of the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot, the worst outbreak of racial violence in the city's history. Whites had done almost all of the bloodletting so far, and authorities feared blacks were plotting reprisals.

As they headed back for the jail with their prisoners, the posse noticed figures lurking in the shadows. An officer ordered them to put up their hands. Someone pulled a trigger. Guns crackled and flashed for five minutes. A white cop and at least two black residents fell dead.

At the Fulton County Courthouse the next morning, one of the policemen, John Oliver, gave an account of the battle to a gathering that included a reporter for The Atlanta Evening News. After the shooting started, he told them, he spotted a man with a gun coming toward him and fired.

"I found him this morning. I had shot him in the stomach. He was an old negro and had a muzzle-loading musket."

The "old negro" was probably George Wilder, a disabled veteran who lived with his wife on nearby Moury Avenue. At 70, he was a former slave who had fought with the Union Army at the end of the Civil War. Thought to be the oldest Atlantan to die in the riot, he lies under a broken tombstone barely a mile from where he was shot to death.

Wilder's grave has become a focal point for a group of Atlantans who plan to commemorate the riot centennial this week. The Coalition to Remember the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot —- representing an array of local colleges, governments, and cultural and faith groups —- is staging a four-day remembrance that will be part symposium and part town hall meeting.

The observance will begin Thursday with a memorial service at old Ebenezer Baptist Church, where the names of dozens of people caught up in the violence will be read aloud. Then a funeral procession will leave for South-View, Atlanta's oldest black cemetery, where an African libation —- a blessing and ceremonial pouring of water —- will be held at the Wilder plot.

"It's the only victim's grave we've been able to find," says historian Clarissa Myrick-Harris, a coalition organizer.

A result of white rage

Unlike the urban disturbances of the 1960s, when black ghettos exploded in frustration, the riots of a century ago were usually the result of white rage. In an era of lynchings, white hysteria over black sex crimes —- real and more often imagined —- occasionally boiled over in mass retribution that resembled the pogroms against Jews in Russia.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, white marauders attacked black communities in Wilmington, N.C.; Springfield, Ill.; Tulsa, Okla.; and a dozen other cities.

Atlanta's descent into a near race war began on Sept. 22, 1906. It was Saturday night, and the newspapers were hawking extras with wildly exaggerated reports of rapes by blacks. Whipped into a frenzy, a crowd of 5,000 downtown started assaulting blacks at random. By the time the violence ended four days later, between 25 and 50 people were dead, and the city's reputation for New South moderation had been badly bruised.

For months, the coalition has been trying to find descendants of people who were affected by the riot for its centennial remembrance. Last winter, the local chapter of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society volunteered to research some of the names. Ten genealogists spent hours poring over archives, squinting at newspaper microfilm and mining Web sites until way past their bedtimes.

"It became personal for me," says one of the researchers, Rhonda Barrow of Lithonia. "No one has told these people's stories."

Between them, the coalition and the genealogists have located the great-great-nephew of a white mob leader, the grandson of a postmaster who was jailed in the riot and the granddaughters of a man who was convicted of killing the white police officer in Brownsville.

"He might have shot him," says one of the granddaughters, Patricia Bearden, a retired schoolteacher in Chicago who is planning to come to the centennial. She remembers her grandfather, Alex Walker, as a thin man in overalls who chewed tobacco and walked with an uneven gait. He was released from a Georgia prison after serving only four years and fled the state, ending up in Chicago.

"Grandpa was a proud man," she says. "He bragged about his part in the riot, but he might have been exaggerating. He liked to drink."

For all their efforts, the genealogists have been unable so far to find a descendant of a person who was killed in the riot.

Most of the known victims were young and had not had a chance to start families. Judging from death certificates, at least eight of them are buried at South-View. Seven lie in unmarked pauper graves.

Only Wilder's is marked. His tombstone, a sliver of age-mottled granite, is broken off at the top. The remnant bears an inscription that's so weathered it's almost impossible to read.

Almost.

Few records left

Most of what's known about Wilder comes from his military and pension records, 182 pages stored at the National Archives in Washington.

The file contains sketchy records of his service in the Union Army, medical documents relating to his application for a disability pension, and a collection of affidavits given by relatives and friends after his wife filed for widow's benefits. The Bureau of Pensions questioned whether George and Isabella actually had been married and conducted an inquiry. Satisfied by their 1875 marriage license, the bureaucrats granted her $12 a month.

The picture of Wilder that emerges from the file is that of a hard-working man with a plague of aches and pains who was, in the words of a federal examiner, "respected by both white and colored acquaintances."

Like many folk then, he could not write his name. He marked his statements with an "x."

Some of the information in the file is contradictory. Wilder's birthplace is given as Bibb County, Ga., or Perry County, Ala. Census records have led the genealogists to believe he might have been born in Clarendon County, S.C.

When the Civil War began, his widow said, George was a slave and belonged to a Wilder family in Macon.

By the end of the war, he was in Alabama. On April 8, 1865 —- the day before Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox —- Wilder enlisted in Selma and became part of the 137th U.S. Colored Troops, a regiment of former slaves from across Alabama and Georgia. In his disability statements, he says he was shot, bayonetted and suffered a gunpowder burn to an eye. He mentions skirmishes near Columbus. Ga., and Mobile, Ala.

Wilder was so proud of his service that he apparently adopted "Union" as a middle name. A piece of his tombstone lying in the grass reads: "George Union Wi" ... the last four letters were on a lost fragment.

In January 1866, Wilder mustered out of the Army in Macon. He eventually moved to a plantation outside Albany and lived with a woman named Lou who bore him a daughter. After Lou died, he married a younger woman, Isabella. They stayed together for the rest of his life and never had children.

In the early 1880s, they migrated to Atlanta, where Wilder guarded leased convict labor at the Chattahoochee Brick Co. At other times, he listed his occupation as farmer, servant and cook.

Wilder applied for an "invalid pension" in 1890, complaining of rheumatism, heart disease and blinding pain behind the eye that had been burned by gunpowder in the war.

Even so, he was still working. Eugenia Stovall, who employed him as a servant at her West Peachtree Street home, vouched for Wilder in a 1900 affidavit: "He is a good faithful man and does all he can, with an energy and spirit that is commendable."

One of best black areas

By 1906, the Wilders were living in a house off Jonesboro Road in Brownsville, just beyond the city limits near the new federal penitentiary. It was one of the area's best black neighborhoods, a mixture of blue-collar and middle-class homes clustered around Clark College and Gammon Theological Seminary, two schools that would later move to the Atlanta University complex in West End.

When the riot began that Saturday night, rumors of a massacre downtown quickly spread to Brownsville. Over the next two days, residents huddled for safety in the seminary chapel, where the school's president pleaded by phone with city officials to send police protection.

The law arrived at sundown on Monday night. According to an anonymous tip, Brownsville was arming itself to retaliate against white Atlantans.

"The people in Brownsville thought those men were coming to kill them," says historian David Fort Godshalk of Shippensburg University in Pennsylvania.

Godshalk investigated the Brownsville shootout for his 2005 book on the riot, "Veiled Visions," and couldn't tell who shot first. The newspapers fell in line behind the police and called it an ambush. But one of the nation's best-known muckraking journalists, Ray Stannard Baker, interviewed residents for a magazine series and concluded that the cops had started it.

One of the first shots struck Fulton County policeman James Heard in the head and killed him instantly. One of his comrades took cover behind his corpse and returned fire.

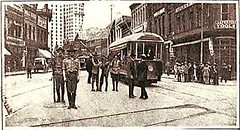

When the battle ended, the police retreated to a white neighborhood and put their prisoners on a streetcar bound for downtown. The car was stopped by a white mob, and two black men bolted. The rabble caught up with them and shot them "to pieces," in the words of one witness. The sight shocked a pregnant white woman who was watching from a nearby porch, and she dropped dead of a heart attack, according to newspaper accounts.

At dawn on Tuesday morning, three companies of state militia invaded Brownsville and rounded up 257 men. One of the soldiers hit the seminary president over the head with a rifle butt.

Wilder's body was found that morning and sent to an undertaker downtown. The coroner listed the cause of death as "gunshot."

Isabella Wilder was more specific when she applied for her widow's pension 12 days later. On the night her husband died, a friend said, she had been away at work, probably as a servant in a private home. But she had seen his corpse. She gave the cause of death as "cuts by knives and gun and pistol shots ... in the hands of a mob."

Unanswered questions

Was Wilder an innocent bystander caught in the crossfire? Did he haul out his Civil War musket and try to defend his home? Did he take a shot at a cop and find himself the target of instant retribution?

No one knows.

Wilder's death resulted in no charges. The Constitution named him as a riot fatality in a five-line brief, but none of Atlanta's newspapers bothered with an obituary.

His widow, however, did leave a testament. It's at his grave in South-View. The inscription on the broken tombstone, unreadable to the naked eye, can be discerned with a careful etching. Underneath his name, age and affiliation with the Odd Fellows fraternal organization, there are three lines of lightly engraved script:

a soldier of the Civil War

was killed in the riot

of Atlanta Sept. 26, 1906

The date is probably wrong —- Wilder is thought to have died on Sept. 24 —- but the sentiment is unmistakable.

"She wants the world to know how he died," says Georgia State University historian Cliff Kuhn, a coalition organizer. "This guy fought for his country and died at a time when people were trying to strip away the rights he had won. She wants people to know. At some level, it's like Emmett Till's mother insisting on an open casket after her son was lynched."

At South-View recently, employees of the National Park Service's Martin Luther King Jr. historic site visited Wilder's grave to make a tombstone etching for an exhibition about the riot. It will open this week on Auburn Avenue, in the same visitors center gallery that four years ago housed a memorable exhibition of lynching photos.

As one of the Park Service employees stretched a carbon paper tight across the old granite, another rubbed a tennis ball over the surface. Forgotten words began to appear like an image on a film negative.

"We're going to tell your story," one of them almost whispered into the stone.

"Even if it is 100 years too late," said the other.

Famed Atlantans remember the riot

Margaret Mitchell

The future author of "Gone With the Wind" was 5 years old and living in a house near downtown Atlanta. When she overheard a neighbor warn her father about possible retaliation by blacks, she imagined another Civil War was starting and fetched an ornamental sword for him to defend the family.

W.E.B. Du Bois

The Atlanta University professor was in Alabama when the riot began. He rushed back to town and stood guard with a shotgun on the steps of South Hall. Du Bois wrote a poem about the riot, "A Litany of Atlanta," in the form of an anguished plea to God: "Red was the midnight; clang, crack, and cry of death and fury filled the air and trembled underneath the stars while church spires pointed silently to Thee."

Joel Chandler Harris

The newspaperman who had become famous for his "Uncle Remus" tales was at home in West End when a gunshot crashed through one of his front windows at 5 a.m. A citizens' patrol had sighted a "disreputable looking Negro," in the words of one newspaper, and chased him, discharging a Winchester rifle. During the riot, Harris sheltered several blacks in his outbuildings.

Walter White

On the night the riot erupted, the future NAACP leader was a teenager riding in a wagon with his postmaster father as he made his rounds through downtown. They witnessed some of the first bloodshed, as the rabble beat a lame barbershop bootblack to death in the street. White told the story in his memoirs.

ABOUT THIS STORY

The riot narrative was drawn from contemporary newspaper and magazine accounts, academic studies and four books published in recent years: "The Atlanta Riot" by Gregory Mixon, "Negrophobia" by Mark Bauerlein, "Rage in the Gate City" by Rebecca Burns and "Veiled Visions" by David Fort Godshalk.

1906 Riot Centennial Events

The remembrance begins at 9 a.m Thursday with the opening of "Red Was the Midnight," an exhibition in the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historic Site visitors gallery.

--At 1 p.m., there will be a memorial service at old Ebenezer Baptist Church, followed by a procession to South-View Cemetery and a graveside service.

--At 7 p.m., the Georgia Association of Black Elected Officials will lead a candlelight vigil through the Old Fourth Ward, where some of the violence occurred, starting at the King gravesites on Auburn Avenue.

--The remembrance continues Friday, Saturday and Sunday with panel discussions, book signings and artistic interpretations at Georgia State University and the Atlanta University Center's Woodruff Library.

For a listing of events: 770-423-6069, http://www.1906atlantaraceriot.org

1 comment:

DEADLINE: How Atlanta's newspapers helped incite the 1906 race riot

By Jim Auchmutey

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Published on: 09/17/06

When civil rights demonstrations embroiled Atlanta during the early 1960s, the institutional memory of another disturbance decades before tugged at the men who ran the city's newspapers.

The press, they knew, had been implicated in the worst racial carnage in Atlanta history: the 1906 race riot.

"All of us at the paper were acutely aware of it," remembers Eugene Patterson, who became editor of The Atlanta Constitution when Ralph McGill rose to publisher. "Mr. McGill and I talked about it. As race relations were heating up again, some of the old-timers around the paper would remind us that this had occurred and that we needed to pay close attention so it didn't occur again."

Patterson was curious about what the Constitution and others had published in 1906, so he dug into the morgue and did some reading. What he found was column after column of overheated stories about black men threatening white women and worse.

"It was terribly sensational," he says. "There was no excuse for it. It was incendiary."

This week, as the centennial of the riot is commemorated in a series of events around the city, there will be no shortage of discussion about the causes of the bloodshed that swept Atlanta a century ago. Academics will debate about race-baiting politics and class tensions and gender roles, but one cause is as obvious as a screaming headline.

"The real spark was newspaper coverage of black sex crimes," says David Fort Godshalk of Shippensburg University, author of a 2005 book about the riot, "Veiled Visions."

Atlanta in 1906 was a fast-growing city of 115,000 with a reputation for progressive leadership. Even then, it was seen as a black mecca —- within the constrictions of the time. The city was rigidly segregated. Lynchings were not uncommon.

Atlanta's four daily newspapers reflected the era to a fault:

--The morning Constitution, founded in 1868, was known as the voice of the New South thanks to the editorship of the late Henry Grady.

--The Journal (1883) was the leading evening paper and stressed local news and crime coverage. (Both papers were under different ownership then; the current owners, Cox Newspapers, bought the Journal in 1939 and the Constitution in 1950.)

--The evening Georgian, a new entry, was the showcase of editor John Temple Graves, a tub-thumping orator who had suggested castrating black rapists.

--The Evening News, another upstart, was the scrappiest of the four and was trying to copy the lurid tabloid style of some of the New York papers.

Two black publications also plied their trade in the city: the weekly Atlanta Independent and the monthly Voice of the Negro.

In the months leading up to the riot, the Journal and Constitution were locked in a political dogfight in which each paper had a dog. The front-runner in the Democratic gubernatorial primary was lawyer Hoke Smith, a kingmaker who had once owned the Journal and counted the paper's editor as his campaign manager. His chief rival, Clark Howell, was editor and principal owner of the Constitution.

Their contest hinged on race. Smith played to whites by proposing laws to disfranchise blacks. Howell said such measures were unnecessary because so few blacks could vote anyway.

There was an unmistakable sexual undertone to the debate, says Atlanta magazine editor Rebecca Burns, author of a new book about the riot, "Rage in the Gate City."

"The message boiled down to this: If you give black men the vote, they're eventually going to want to be with your wives and daughters."

As the campaign reached a head in the late summer of 1906, a series of alleged sexual assaults seized the newspapers' attention. That August and September, the press trumpeted a dozen "outrages" by black men. Historians agree that perhaps two-thirds of the cases were unfounded and did not involve crimes.

Nevertheless, the stories almost always made the front page, and the suspect's race was invariably noted in the headline:

Girl Jumps Into Closet To Escape Negro Brute

Bold Negro Kisses White Girl's Hand

Half Clad Negro Tries To Break Into House

The text routinely referred to suspects as "fiends" and "black devils."

"All of the papers carried these stories," Godshalk says, "but the Evening News and the Georgian really went overboard."

Fanning the flames

The News was particularly obsessed. Editor Charles Daniel applauded lynchings and called for reviving the Ku Klux Klan. He offered a reward for the capture of one assailant, got himself appointed a special deputy sheriff and proposed a News Protective League of vigilantes to defend white women.

On the third Friday of September, as the papers hyped another incident, the News ran an editorial headlined: "IT IS TIME TO ACT, MEN."

They acted the following day.

On Saturday, Sept. 22, downtown was crowded with people come to town for the weekend. Through the afternoon and evening, newsboys from every paper except the Constitution hit the sidewalks with extra editions about four new assaults. The stories were based on flimsy reporting —- one woman called police because she had seen a black man outside her window and become frightened —- but that hardly mattered.

Mobs of whites began to attack black people on the streets. The violence spread and continued off and on for four days. At least 25 people —- almost all of them black —- died. A thousand black residents fled the city.

The newspapers denounced the mob, but none of them examined their role in goading it into action. The Constitution at least considered the possibility.

"The tragic climax of Saturday night was conclusive evidence of the power of the press over public sentiment," the paper mused, distancing itself from the fulminations of its evening brethren.

Nor did any of the papers seriously question whether their reporting on black crime had been founded on fact instead of prejudice and hysteria.

"The papers all basically blamed black people for what happened," Burns says.

Other dailies were more skeptical.

"Atlanta," The New York Sun commented, "is in greater danger from the brutal license of yellow journalism than the lust of the negro."

In the aftermath of the riot, two Atlanta publications —- one white, one black —- paid for their actions. One became scapegoat, the other a martyr.

J. Max Barber, editor of the Voice of the Negro, was infuriated when he read a piece in The New York World blaming the riot on "a carnival of rapes" by black men. But he wasn't surprised when he saw the name of the author: the Georgian's Graves. Barber fired off a telegram in response that was published in the World under the signature "A Colored Citizen."

Barber wrote that craven politicians and irresponsible newsmen, not black criminals, had caused the riot. But he also claimed that some of Hoke Smith's followers had blackened their faces and staged assaults in an effort to arouse support for their candidate.

Atlanta leaders were enraged by the unfounded charge. The telegram was traced to Barber, and he was told to either retract his statement or face prosecution for slander.

"I did not care to be made a slave on a Georgia chain gang," Barber wrote. So he fled to Chicago with his printing press and eventually settled in Philadelphia, where he became a dentist and a stalwart in the local NAACP.

Some escape censure

As for the scapegoat, at least there was a degree of justice involved. Within a week of the riot, a Fulton County grand jury censured the evening dailies for their scurrilous extras, singling out the News by name. The paper ran the story a day late under the disingenous head: "The News Condemned For Publishing News."

But it wasn't just the grand jury that was sore at the News. Atlantans cooled to the paper and its circulation dropped. That winter, creditors forced the business into receivership and its carcass was snatched up by its onetime bitter rival, the Georgian.

"The News became the whipping boy," says historian Gregory Mixon of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, author of "The Atlanta Riot." "I think all four papers should have been censured."

In 1939, former Ohio Gov. James M. Cox bought and closed the Georgian. Only two Atlanta newspapers —- the Journal and Constitution —- survived long enough to learn the lessons of 1906.

MORE ON THE RIOT

A panel discussion on race and the media will be held next weekend as part of the centennial events planned by the Coalition to Remember the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot. Participants include Atlanta Journal-Constitution editorial page editor Cynthia Tucker and Atlanta magazine editor Rebecca Burns, author of a new book about the riot, "Rage in the Gate City." 9 a.m. Saturday at the Atlanta University Center's Robert W. Woodruff Library.

http://www.1906atlantaraceriot.org

THE RUN-UP TO RIOTING

Newspaper reports, often on the front page, were considered the spark of the 1906 race riot. The Constitution, in condemning the evening newspapers, wrote: "The tragic climax of Saturday night was conclusive evidence of the power of the press over public sentiment."

Post a Comment