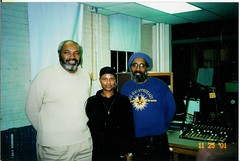

Open Forum Co-Hosts (left to right), Abayomi Azikiwe, PANW Editor, Titilayo Akanke & Malik Yakini. Photo taken at WDTR, 90.9 FM in Detroit (Nov. 25, 2001)

Originally uploaded by panafnewswire.

2005 Allied Media Conference Featured Panel on the History of

Radical Media in Detroit

Charles Simmons & Abayomi Azikiwe spoke on alternative press

outlets

By a Pan-African News Wire Correspondent

Allied Media Conference web site:

http://alliedmediaconference.com

Bowling Green, OH, 18 June, 2005 (PANW)--A national

conference on the role of alternative media was held during

the weekend of June 17-19 at Bowling Green State University.

Entitled the "Allied Media Conference, New Solutions to Old

Problems", the three day event showcased a variety of

spokespersons within the broad spectrum of radical

communications outlets and networks that exist today across

the United States.

Individuals and organizations representing community radio

stations, press agencies, publishing houses, foundations,

youth centers, magazines, journals and popular art put on

displays and held workshops and panels on the experience they

have acquired over the recent period in countering the

monumental impact of an ever increasing concentration of

ownership and programming in the corporate-controlled media.

Some of the panels that were held addressed topics such

as: "Are Our Messages Reaching the Right Audiences?; Zine

Reading; Grassroots Fundraising; Microradio: Overview &

Operations, etc. Many of the speakers represented the

burgeoning movement of activists who are seeking means to not

only get out the news and information that needs to be seen

and heard but to also influence social change in the

contemporary era.

Perhaps one of the most interesting panels took place on June

18 which featured Charles Simmons, professor of journalism

and law at Eastern Michigan University and Abayomi Azikiwe,

the editor of the Pan-African News Wire and a broadcast

journalist, who both examined the history of radical media in

the city of Detroit.

Charles Simmons began the discussion by conveying his own

personal experiences in the United States Air Force during

the early 1960s. Simmons had expressed an unwillingness to

participate in American plans to invade Cuba after the Bay of

Pigs incident in 1961 and the missile crisis which occured in

October of 1962.

After being threatened by his superior officers, he was

placed in military detention along with other dissidents in

the service. It was during this period that Simmons began to

read socialist literature and anti-war tracts through a study

group established by those who were resisting the cold war

policy of the government. Prior to this time period he had

spoken with older GIs who had participated in the Korean war.

These soldiers held a totally different perspective on the

war than what had been promoted by the Eisenhower

administration.

"I thought we had won the war, but when I spoke with people

who had actually gone there to fight, they kept talking about

how they had been beaten by the Korean and Chinese military

forces," Simmons said.

In regard to US-Cuba relations, Simmons said that "we had

seen the newsreels of Malcolm X meeting with Castro during

his visit in 1960 to Harlem and therefore we could not be

against Castro if he was liked by Malcolm."

"We never had a fair media in the African-American community

other than our own," said Simmons. "The media's handling of

the African-American community has been unfair from the

beginning. It has been racist, it was biased in every way we

can think of, it was exclusive and in many communities as it

relates to African-American societies, we only had some

mention of the African-American community one day a week.

Many of the mainstream papers would have a section called

the "Colored Section" or the "Negro Section" and it was

basically a discussion of some level of crime, entertainment

and sports." According to Simmons, "it really hasn't changed

since then, except we have more days of it and it is

broadcast to cable and satellite."

"We were dealing with lynchings in that period and it really

hasn't been that long ago. I can remember when Emmit Till

was lynched. We were the same age. He was visiting his

grandparents in the South and I would do the same thing."

Simmons then went on to discuss some of the organizations in

the African-American community that have published newspapers.

He mentioned the Nation of Islam which published the Muhammad

Speaks.

After his release from the military he returned to Detroit

and attended Wayne State University. He became a student

activist with UHURU, one of the early militant organizations

on campus during the 1960s. "We started to produce leaflets

and we mimeographed them right on the campus. At that time

people didn't get a lot of flyers and junk mail. We were not

saturated with a lot of information. Television wasn't that

old and experienced as it is now," Simmons continued.

"We published a newsletter called the Black Vanguard that was

circulated in the factories. Also we put out a publication

for students called The Razor. We were radicalized more by a

trip we took to Cuba in 1964 designed to challenge the State

Department's travel ban on the country. We were fortunate to

meet Robert Williams there who was in exile from the struggle

in the United States. We also met Che Guervara and got to

talk with him. We got to play baseball and talk to Fidel

Castro. There were a lot of young people in Cuba from the

ANC (African National Congress) and the PAC (Pan Africanists

Congress) from South Africa, there were people from Namibia

and other countries."

Later the political activities of people in Detroit led to

the organization of the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement

(DRUM). Simmons discussed how the organizing expanded to

other work places throughout the area. Eventually in 1969,

the League of Revolutionary Black Workers (LRBW) was

formed. "There were newsletters printed in each plant named

after each revolutionary union movement. When we had protests

they were against both the company and the unions. We wanted

to desegregate the leadership in the company and the union."

Simmons who later became an international correspondent for

the Associated Press, also wrote for the Muhammad Speaks. He

then discussed how the League of Revolutionary Black Workers

took over the campus newspaper at Wayne State University, the

South End, in 1968-69 and ran it as a city wide publication

that was heavily circulated in the plants, the community and

the schools.

Alternative media in post-industrial Detroit

Abayomi Azikiwe then spoke about the changing character of

radical media in Detroit beginning in the middle to late

1970s.

"The whole evolution of radical and alternative media in

Detroit was an outgrowth of the popular struggles of African

people in the United States and around the world which took

place coming out of the post World War II period--and of

course becoming more intensified during the 1960s and early

1970s. As Charles talked about during the 1960s, the African-

American community was in a state of popular revolt. For

example, if you read the Kerner Commission Report on Civil

Disorder, which was published in the spring of 1968, it

indicates that the previous year there had been over 164

rebellions in the United States that were principally led by

African-Americans."

"In 1968, right in the aftermath of the assassination of

Martin Luther King, Jr., over 125 cities had popular

rebellions during that particular time period. That extended

throughout the summer of 1968. This was also paralleled by a

rise of activism in the white community, particularly among

the youth. Within the so-called Hispanic community, mainly

among Puerto Ricans and Mexicans. Also among the Asian-

American youth as well, largely out on the west coast."

According to Azikiwe, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was

assassinated as a result of his evolving position linking the

Vietnam War with the struggle for civil and human rights in

the country. After 1965 the civil rights movement began to

reassess its position to address the economic conditions

facing African-Americans. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and

the Voting Rights Act of 1965 were tremendous victories but

they could not totally address the socio-economic crisis in

the African-American communities across the country.

"All of this coincided with the so-called Counter-Intelligence

Program (COINTELPRO). This program was designed

by the FBI during the 1950s primarily to crush the Communist

Party and the left in the United States. However, by the

early 1960s with the burgeoning civil rights movement, most

of the efforts that emerged from the Counter-Intelligence

Program were geared towards stifling and ultimately smashing

the black liberation movement, both the civil rights aspects

of the movement as well as the black power and black

revolutionary aspects of the movement," Azikiwe continued.

"So by 1969-70, we had hundreds of members of the Black

Panther Party and other organizations that had been

incarcerated, who had been indicted on criminal charges. So

we had a whole attempted criminalization of the African-

American liberation struggle."

"At the same time, we had burgeoning national liberation

movements in Africa. In Guinea-Bissau you had the PAIGC

(African Party for the Independence of Guinea). In Mozambique

there was FRELIMO (Mozambique Liberation Front). In Angola

there was the MPLA (Popular Movement for the Liberation of

Angola). In Namibia there was the South-west African Peoples

Organization (SWAPO). In Zimbabwe you had the Zimbabwe

African National Union (ZANU), and the Zimbabwe African

Peoples Union (ZAPU). In South Africa it was the African

National Congress (ANC). All of these organizations saw the

United States as being a principal impediment to their own

excercise in self-emancipation."

"The African-American liberation movement in the United

States attempted to hook up with the Vietnamese liberation

struggle as well as the national liberation movements in

Africa and other parts of the so-called Third World," Azikiwe

stated. Illustrating the significance of the struggle in the

United States during this period, Azikiwe recalled how the

North Vietnamese government had offered to release all United

States prisoners of war in exchange for the Americans

releasing both Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, the founders

of the Black Panther Party for Self-defense. Seale and Newton

were incarcerated during the fall of 1969 when the offer was

made. The United States government under the Nixon

administration immediately rejected the notion of linking the

war in Vietnam with the black liberation struggle in the

United States.

During the early 1970s there were numerous splits within

various revolutionary organizations. It is Azikiwe's

contention that these fissures were related to the pressure

exerted against the black liberation movement by the Counter-

Intelligence Program. All of these organizations had

independent journals.

He cited the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee's

(SNCC) newsletters: The Student Voice and the The Movement.

In addition, he spoke about the Black Panther newspaper, the

Inner City Voice, published by the LRBW in Detroit, which

lasted for several years.

These publications were viewed as a threat by the federal

government. According to Azikiwe, J. Edgar Hoover targeted

the Black Panther newspaper for disruption because it was the

most effective tool the party had during its peak between

1968 and 1971. The newspaper's circulation was reported to

be a quarter-of-a-million copies every week.

"In the Black Panther newspaper you could not only find

articles dealing with the struggle in the United States, you

could also find international news. They had articles by Kim

Il-Sung, Mao Tse-Tung. They had information about the

struggles in South Africa, in Congo, in Congo-Brazzaville, in

Cuba. In fact Eldridge Cleaver, who was the Minister of

Information of the Black Panther Party at that time, when he

fled the United States in 1968, the first place he went after

he stopped in Canada, was Cuba. Robert Williams had also

been there earlier," Azikiwe continued.

Azikiwe mentioned that the Muhammad Speaks, which Charles

Simmons was a correspondent for, was one of the best

newspapers coming out of the country during this time

period. He mentioned that there would be some information on

the religous views of the Nation of Islam under Elijah

Muhammad. However, the bulk of the paper was objective news

coverage of national and international issues confronting

African people internationally.

"There were articles in the paper by Charles Howard, who was

the United Nations correspondent for the Muhammad Speaks.

There were articles by Shirley Graham DuBois, who was the

widow of W.E.B. Dubois, then living in Cairo and the People's

Republic of China. All types of great information, in fact

the Muahmmad Speaks is still available on microfilm for

people who want additional information about that period. If

you are really serious about doing historical studies about

the 1960s and 1970s, the Muhammad Speaks is an excellent

primary resource document. "

Azikiwe went on to discuss the impact of the Counter-

Intelligence Program on the black alternative press during

this era.

"Many of those organs that I mentioned earlier dissolved.

For example, the Movement stopped publishing around 1970.

The Black Panther newspaper after the split in 1971 continued

but it did not have the same impact as before. The newspaper

published until 1980. The Inner City Voice stopped

publishing around 1971. And the Muhammad Speaks, as a result

of the death of Elijah Muhammad in 1975, his son, Wallace

Muhammad, took over the organization in 1975 and about six

months after the death of Elijah Muhammad, tremendous changes

took place within the Nation of Islam. They closed down a lot

of their businesses across the country and one of the

casualties of that whole shift in the Nation of Islam was of

course the dissolution of the Muhammad Speaks newspaper.

This was a major loss to the African-American community and

the world."

"The South End newspaper was taken over by the administration

in 1973 at Wayne State University. They set it up where in

fact students were not able to control the editorial

direction of the newspaper. By the time I got to the

University in the late 1970s, all of these things had been

pretty much eliminated or were in decline. Joining black

student organizations during that time period there was a

void. It was in the aftermath of the tremendous impact of the

Counter-Intelligence Program: the jailing of hundreds of

activists in this country, the driving into exile of many

others. The fact that the newspapers had been shut down and

gone out of business created a tremendous void as it related

to radical and revolutionary ideas during that period."

"During that period," Azikiwe continued, "you had the

development of smaller, more limited publications. For

example in 1982, we created African Viewpoint, a newsletter.

It only published a few issues dealing with the struggles in

Africa and the anti-racist struggle in the United States.

Later Pambana Journal was created which published for over 15

years. By the mid-1990s, with the development of the

internet technologies, this phenomena had a tremendous

impact on the movement building activities."

Azikiwe attributes the mass mobilizations around the defense

of Mumia Abu-Jamal and the anti-war movement to the effective

use of the world wide web. "Today we are in a position to

effectively compete with the corporate media. We have to

utilize technology to advance the popular struggles to a new

level of development in the United States.

During the question and answer period, one audience

particpant lamented the lack of knowledge by many younger

people in Detroit about the tremendous historical legacy

within the city. Azikiwe pointed out that this information is

not taught in the schools or advanced through the mass media

and that it is the responsibility of the activists community

to find creative ways of telling the true peoples' history of

the country.

Another question related to the status of educational radio

in Detroit which has been leased to Detroit Public Television

for management purposes. Azikiwe, who was a co-host along

with Malik Yakini and Titilayo Akanke on the Open Forum

weekly radio program over Detroit Public Schools radio, had

there program eliminated do to the changes stemming from the

current budget crisis in the city and the political

conservativism of the state-controlled school board.

Azikiwe stated that "we have to make the leasing of 90.0 FM a

political issue in the upcoming school board elections, the

first in six years. The station was bought and paid for by

the taxpayers of Detroit and they should control its

programmatic direction. Public television does not broadcast

to people in the city and therefore should not be in charge

of a Detroit educational station. We are demanding full

restoration of community programming over educational radio,"

he declared.

In concluding the panel, Azikiwe encouraged the media

activists present and said that "the days of independent

media are here."

No comments:

Post a Comment